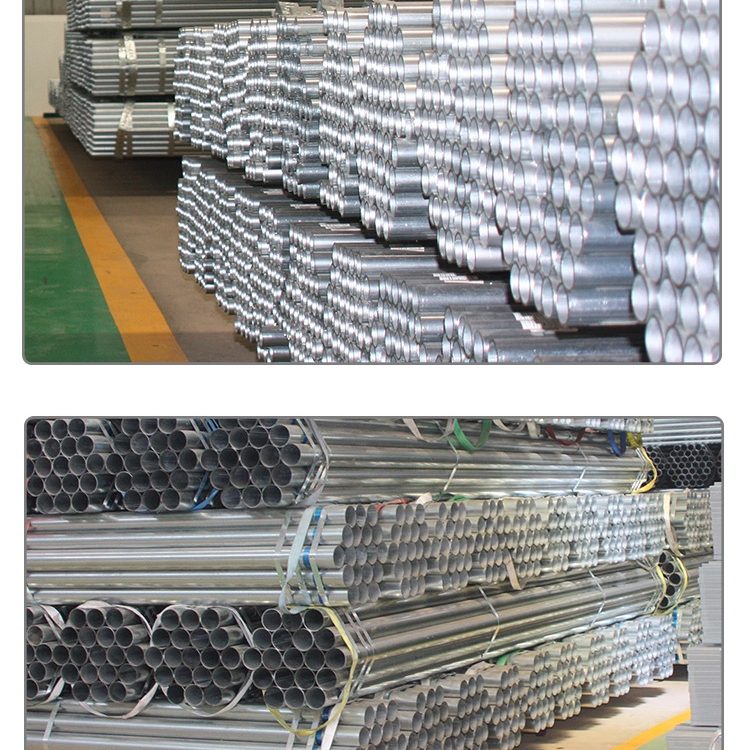

Galvanized Steel Schedule 40 Pipe for Scaffolding

December 30, 2025

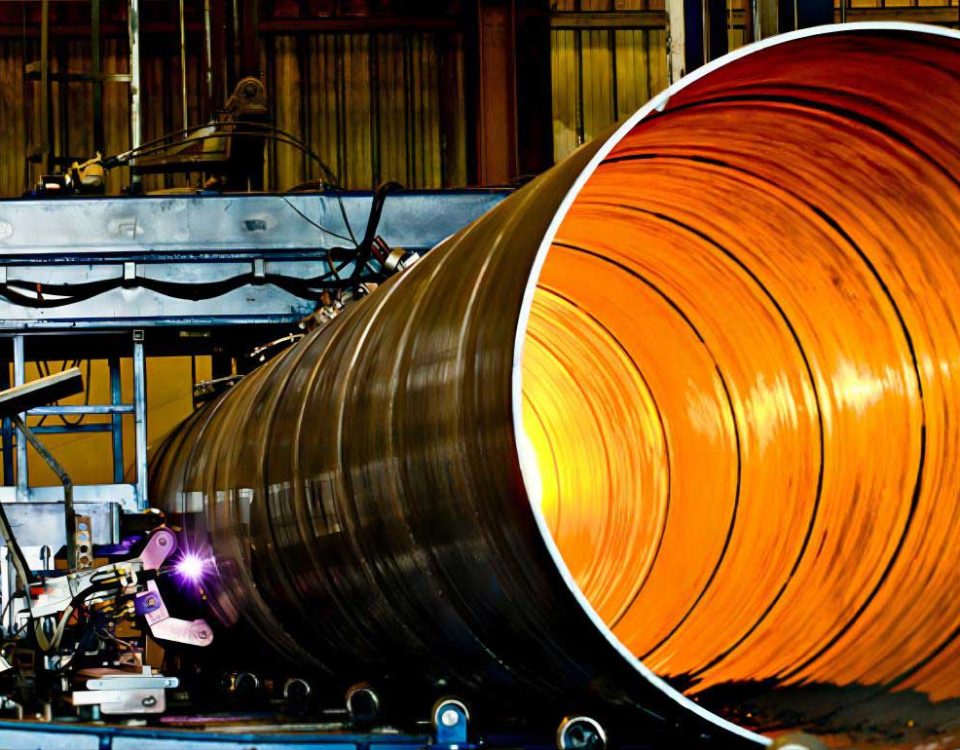

French NF A49-721 standard 3-layer 3LPP coating steel pipe

January 5, 2026Internal Monologue: The Weight of Structural Decisions

When I begin to weigh the differences between Schedule 40 and Schedule 80 in a scaffolding context, I immediately start calculating the trade-off between material density and the physics of gravity. It is a common misconception in the field that “thicker is always better.” In my mind, I see a scaffold not just as a static frame but as a living organism of steel that must support its own weight—the “dead load”—before it can even begin to safely carry the “live load” of masons, tools, and materials. Schedule 80 pipe is significantly heavier because the wall thickness increases while the outer diameter stays constant; for a standard 1.5-inch nominal pipe, we are looking at a jump from a 3.68mm wall to a 5.08mm wall. This extra steel adds roughly 30% more weight per foot. If you are building a high-rise scaffold, that 30% increase in self-weight translates to a massive increase in the vertical pressure exerted on the base plates and the mudsills. I’m thinking about the “Slenderness Ratio” ($L/r$); while the thicker wall of Schedule 80 slightly improves the radius of gyration, the primary failure mode in scaffolding isn’t usually the crushing of the steel itself, but rather the buckling of the entire assembly. Schedule 40 strikes that perfect metallurgical “sweet spot” where the moment of inertia is sufficient to prevent local buckling without the pipe becoming so heavy that it necessitates specialized heavy-duty transport and excessively expensive foundational support. Furthermore, I’m contemplating the compatibility of the fittings. Scaffolding couplers—the “right-angle” and “swivel” clamps—are precision-engineered to bite into a specific range of steel hardness and thickness. If the pipe is too rigid (like Sch 80), the clamp might not “seat” with the same frictional grip as it does on the slightly more compliant Sch 40 surface. Then there’s the testing. When I look at the ASTM A53 or the EN 39 protocols, I see a rigorous gauntlet designed to find the smallest molecular flaw. The flattening test, for instance, isn’t just a physical squishing of the pipe; it is a search for microscopic inclusions in the weld seam. I’m imagining the pipe being compressed until the distance between the plates is just a fraction of the diameter—if the weld doesn’t hold up under that extreme tensile stress on the outer radius, the entire batch is compromised. It’s about the “ductility reserve.” In the European EN 39 standard, the focus shifts slightly toward the chemistry of the galvanization and the strictness of the straightness tolerances, which are often tighter than general-purpose plumbing pipe. We aren’t just making tubes; we are making the safety net for human lives.

Comparative Analysis and Global Safety Standards for Scaffolding Pipe

Schedule 40 vs. Schedule 80: The Engineering Trade-off

In the selection of galvanized steel pipe for scaffolding, the primary conflict is between Structural Rigidity and Systemic Load-Bearing Capacity. Schedule 40 and Schedule 80 represent two distinct philosophies in pipe design. Because the Outside Diameter (OD) of a nominal pipe size remains constant across different schedules to ensure compatibility with standardized fittings, the increase in wall thickness in Schedule 80 occurs internally, reducing the pipe’s Bore (ID).1

From a purely mechanical perspective, the Moment of Inertia ($I$) is a measure of a pipe’s resistance to bending. For a hollow cylinder, $I$ is calculated as:

where $D$ is the outside diameter and $d$ is the inside diameter. While Schedule 80 has a higher $I$ and thus greater resistance to bending, it also significantly increases the Dead Load ($G$). In scaffolding, the maximum height of the structure is limited by the compressive strength of the standards (the vertical pipes). If the pipes themselves are 30% heavier, the total height reachable before the base pipes reach their yield point is drastically reduced.

Table 4: Mechanical Comparison (1.5″ Nominal Pipe Size)

| Property | Schedule 40 (Standard) | Schedule 80 (Extra Strong) | Impact on Scaffolding |

| Wall Thickness | 3.68 mm (0.145 in) | 5.08 mm (0.200 in) | Sch 80 is 38% thicker. |

| Weight per Meter | 4.05 kg/m | 5.23 kg/m | Sch 80 increases dead load by ~29%. |

| Internal Diameter | 40.89 mm | 38.10 mm | Affects compatibility with internal joint pins. |

| Bending Resistance | Moderate/High | Very High | Sch 40 is sufficient for 95% of access tasks. |

| Handling | Manual lift possible | Often requires mechanical assist | Affects labor cost and worker fatigue. |

For most industrial and commercial scaffolding, Schedule 40 is the global preference. It provides the necessary safety factors while maintaining a weight that allows for efficient manual assembly and dismantling. Schedule 80 is typically reserved for specialized “Heavy-Duty” shoring towers where the pipes are used as massive columns to support the weight of wet concrete or heavy machinery.

Global Testing Protocols: The ASTM and EN Frameworks

To ensure the reliability of scaffolding pipe, it must adhere to specific testing protocols that simulate the extreme stresses of a construction site. The two most prominent standards are ASTM A53 (typically Grade B) in the Americas and EN 39 / EN 10219 in Europe and much of the international market.

1. The Flattening Test (ASTM A53)

This is the most critical test for Electric Resistance Welded (ERW) pipes. A sample of the pipe is placed between two parallel plates and compressed. For scaffolding pipe, this is done in two stages:

-

- Stage 1: Focuses on ductility. The pipe is flattened until the distance between the plates is approximately 2/3 of the original OD. The weld must not show any cracks.

- Stage 2: Focuses on the soundness of the steel. The pipe is flattened further until it is nearly closed. This ensures that the steel is free from internal laminations or “dirty” inclusions that could cause a sudden split under pressure.

2. The Cold Bend Test

Scaffolding often involves the use of “bent” tubes for architectural scaffolding or specific structural bypasses.2 The bend test involves wrapping the pipe around a cylindrical mandrel (usually 6 to 12 times the pipe’s diameter). The pipe must reach a 90-degree angle without developing any surface cracks or “orange peel” textures, which would indicate a coarse grain structure or poor heat treatment.

3. Straightness and Dimensional Tolerances (EN 39)

The European EN 39 standard is particularly strict regarding the physical geometry of the pipe. A scaffold pipe that is slightly bowed acts as a “pre-curved” column, which significantly lowers its buckling load.

- Straightness: The deviation from a straight line must not exceed 0.002L (where L is the length). For a standard 6-meter pipe, the deviation must be less than 12mm over its entire length.

-

Mass Tolerance: The actual weight of the pipe must not vary from the theoretical weight by more than $\pm 7.5\%$, ensuring that the material hasn’t been “thinned out” during the rolling process to save costs at the expense of safety.

4. The Zinc Adhesion Test (ASTM A123 / A153)

Because scaffolding pipes are repeatedly hit by hammers and scraped by steel couplers, the galvanization must be more than just a surface layer. The “Hammer Test” or “Preece Test” ensures that the zinc-iron alloy layers are properly formed. If the coating is too thick and brittle (due to high silicon levels), it will “spall” or flake off, leaving the underlying steel vulnerable to rapid localized corrosion (pitting), which can hide structural weaknesses under a layer of rust.

Table 5: Summary of Global Safety Standards for Scaffold Pipe

| Standard | Region | Key Focus | Primary Grade |

| ASTM A53 | USA/International | Multi-purpose structural integrity | Grade B (240 MPa Yield) |

| EN 39 | Europe/UK | Specific scaffolding requirements | S235GT (235 MPa Yield) |

| AS/NZS 1576 | Australia/NZ | High-durability and safety factors | Grade C250/C350 |

| JIS G34443 | Japan4 | Earthquake-resistant ductility5 | STK 400 / STK 5006 |

Final Engineering Recommendation

For your company’s product—Galvanized Steel Schedule 40 Pipe—the competitive advantage lies in the consistency of the normalizing heat treatment and the purity of the zinc bath. By adhering to Grade B specifications under ASTM A53, you provide a pipe that offers a 20% higher yield strength than the basic S235 steel commonly found in “budget” scaffolding. This extra margin of safety is what allows engineers to confidently design taller, more complex scaffold structures.